Brushstrokes in Fiction: Exploring Art History Through the Novel

Fiction and painting have long been kindred spirits. Both are acts of composition, selection, and interpretation. A writer arranges sentences just as a painter arranges pigments: shaping perception, summoning emotion, and conjuring a sense of reality that is always, in some way, illusion. It’s no wonder, then, that many novelists turn to painting and art history not only as a recurring motif—an organizing principle through which the novel can explore deeper themes such as beauty, mortality, memory, and the nature of perception itself. For authors who aspire to write novels that weave art into their narrative fabric, the work can be deeply rewarding but also structurally and thematically challenging. This is precisely the kind of project where a book coach can be invaluable: helping the writer navigate research, build layered motifs, and ensure that the visual world of art deepens rather than distracts from the story.

One of the most well-known novels to foreground painting as both subject and metaphor is Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier. Set in 17th-century Delft, the novel imagines the story behind the creation of Vermeer’s iconic painting of the same name. While the historical framework is evocative and meticulously researched, it is not merely the setting or even Vermeer himself that provides the emotional weight of the novel. Instead, the act of painting becomes a way to explore power, class, silence, and the politics of the gaze. The unnamed girl, later known to us as Griet, serves both as muse and invisible laborer, her interior life echoing the stillness and restraint of Vermeer’s compositions. Through the novel’s exploration of the painter-model relationship, Chevalier gives readers a meditation on intimacy, control, and the way art both reveals and erases its subjects. A writer attempting something similar must juggle period detail, artistic process, and an understanding of the visual symbolism of a specific painter’s style. A book coach can help balance these elements, ensuring that the emotional arc of the novel is not lost amid the historical research or aesthetic commentary.

Another luminous example is The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. At the heart of this sprawling novel is a small 17th-century painting by Carel Fabritius—The Goldfinch—which the protagonist, Theo, steals amid the rubble of a terrorist attack. The painting becomes both relic and burden, a surrogate for the mother he lost and a symbol of the fragility of beauty in a shattered world. Tartt threads the history of the painting throughout the novel’s labyrinthine structure, linking ideas about the permanence of art with the impermanence of life. What is so striking about Tartt’s use of art is how seamlessly she integrates painterly themes into the psychology of her characters. The painting is not a passive object—it becomes a moral mirror, reflecting Theo’s guilt, desire, and search for meaning. For authors intrigued by the narrative potential of art objects, working with a coach can offer a critical outside eye to ensure that metaphor does not become overdetermined, and that character development remains at the forefront even when plot is tied to symbolic artifacts.

Michael Frayn’s Headlong takes a more satirical approach to art history. The novel follows a scholar who believes he has discovered a lost painting by Bruegel and becomes entangled in an obsessive quest to acquire it. The novel is a comic romp through art theory, greed, and self-deception, and yet it is also a carefully constructed philosophical inquiry into the relationship between image and history, surface and meaning. Frayn’s narrator becomes increasingly unreliable, and the reader is drawn into the question of how we interpret images—and whether that interpretation can ever be disentangled from our own desires. Writing fiction that engages with art theory in this way without becoming didactic is no small task. A book coach can help an author maintain tonal control, sharpen voice, and construct a narrative in which art history lends itself to the dramatic tension of the story.

Sarah Hall’s The Electric Michelangelo follows a tattoo artist in early 20th-century England, and while it is not about classical painting, it is deeply engaged with questions of the body as canvas and the permanence of visual marks. Hall’s lush, evocative prose often seems to mimic the swirling, sensual textures of painting itself. The novel asks: What does it mean to inscribe a life story onto flesh? How does visual art connect to memory, desire, and trauma? Here, the influence of art lies in language as much as in content. Writers seeking to emulate this painterly use of prose often benefit from coaching that focuses on rhythm, image, and sensory detail to achieve the balance between atmosphere and narrative momentum.

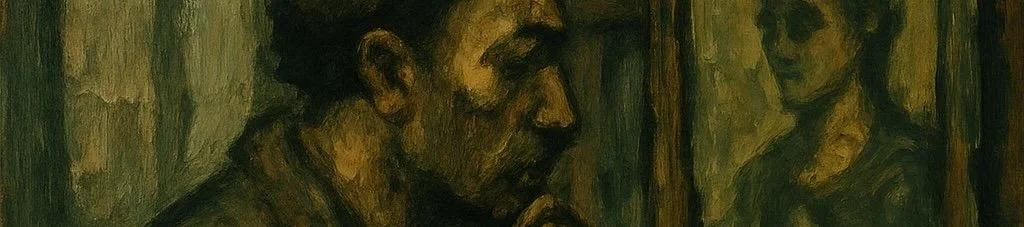

Some novels engage with art through biographical fiction, using real painters as characters to explore artistic vision from the inside out. Irving Stone’s Lust for Life, a fictionalized account of Vincent van Gogh’s life pioneered a form of narrative that connects emotional suffering, artistic genius, and historical fidelity. More recently, novels like I Always Loved You by Robin Oliveira, which chronicles the tumultuous relationship between Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas, or Dominic Smith’s The Last Painting of Sara de Vos, which weaves together three timelines linked by a 17th-century painting, have brought new sophistication to this genre. Writing such novels often involves extensive interdisciplinary research on artistic techniques, biographical context, and art market politics. For writers drawn to this kind of work, book coaching offers not only structural support but also strategic planning—how to synthesize fact and fiction, how to choose the most emotionally resonant scenes, and how to pace the unfolding of historical detail so that it serves character rather than overwhelming it.

Novels that incorporate painting and art history succeed when they do not merely use art as window dressing but treat it as a living metaphor, a philosophical inquiry, or a structuring principle. Whether a writer is crafting an imagined life of a forgotten artist, constructing a mystery around a lost painting, or simply using the language of color and texture to shape their prose, the act of writing such novels demands both creative vision and control. Research must be accurate but not pedantic. Symbolism must be rich but not heavy-handed. And the emotional journey of the characters must remain central even when the plot or theme leans heavily on visual art.

For writers embarking on this kind of literary project, book coaching can offer the kind of sustained, personalized guidance that makes the difference between an ambitious idea and a fully realized novel. A coach helps you refine your concept, clarify your themes, and shape a manuscript that does not merely describe art but enacts its own aesthetic integrity. Writing about painting is an act of translation—from image to word, from color to syntax, from stillness to motion. To do it well is to see with more than the eyes. It is to write, as painters paint, with attention to detail, emotion, and meaning. And with the right support, your novel can become not just a reflection of art history—but a work of art in its own right. Whether you're at the very beginning of your novel or deep in revisions, a book coach is a collaborative partner who understands not just how to write, but how to think like an artist.